Moving On

A version of this story originally ran on BusinessInsider on Oct 28, 2020.

A deep blue sky stretches overhead as Tanker 60, a Douglas DC-7 fire bomber with Erickson Aero Tanker, gleams in the southern Oregon sun at the Medford Air Tanker Base. The airplane’s rounded tail towers over the otherwise empty ramp, emblazoned with its radio call sign: a big, green “60”. Four piston-powered engines, their propellers synced in near-perfect alignment with one another, look especially sharp. The bulbous orange fire retardant tank sticks out conspicuously, while its pointy white nose feels decidedly aggressive.

Captain Ron Carpinella, a decades-long veteran of the airplane, is walking confidently around it, busily performing a preflight check. His eyes dart around at an efficient but attentive pace, looking for any issues that might crop up during flight. His hands do the follow-up work: giving the barn-door-sized flaps on the right wing a little wiggle; stopping to add a hit of WD-40 to the aging landing gear. It is a ritual he has done hundreds, if not thousands, of times.

“But today is probably going to be its last hurrah,” he says from the cockpit, surrounded by a dizzying array of buttons, dials, and circuit breakers.

The airplane looks like a relic, inside and out, because it is one. Built over 60 years ago, it is one of only a handful of four-engined, piston-powered airplanes left in the world. And among the DC-7 family, it is the last airworthy copy altogether. At least for a few more hours.

—–

Sleek and fast, the DC-7 was, when it debuted in 1953, the flagship of the US airline industry. It cut its teeth flying the first coast-to-coast nonstops in the US, connecting New York to Los Angeles at a then-record pace of eight hours one way.

It soon took its prowess for speed across the oceans too. By 1955, airlines like Pan Am flew the plane from New York and Boston to London and Paris in under ten hours, almost two hours faster than most of its competitors.

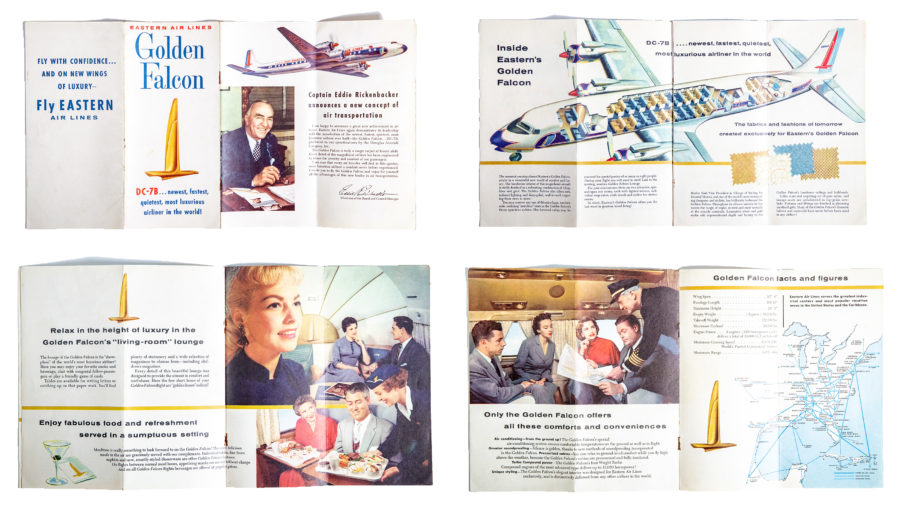

Tanker 60 started its life with Eastern Air Lines in 1958, and likely spent its early years flying up and down the eastern seaboard and into the Caribbean. A photo of a postcard of the plane, pinned in the company’s Medford office, shows as much: Tanker 60 on layover in Miami, adorned in its original Eastern Air Lines “Golden Falcon” livery.

For all of its achievements, the reign of the DC-7 was short-lived. Tanker 60 rolled off the line only three months before Douglas’ first jetliner, the DC-8, began flight-testing. Boeing’s game changing 707 jet was in service by the end of the year. The jets cut flight times dramatically. Transatlantic crossings went from nine hours on the DC-7 to six on the jets; New York to LA dropped from eight to five. Seemingly overnight, the airplane’s main claim to fame—its speed—evaporated. The line shut down in 1958.

“The DC-7 is the Zenith of piston-powered commercial air travel,” said co-pilot Scot Douglas. “But the next step moved on to the jet.” The reign of the piston-powered passenger plane was over.

Airlines seemingly couldn’t ditch them fast enough, and by the mid-1960s they were largely gone from mainline US carriers. Tanker 60 wasn’t an exception: it was ushered out the door from Eastern in 1966.

It likely would have been relegated to a mere footnote in aviation history had it not stumbled into its calling as an air tanker in the 1970s, a job in which the airplane excelled.

“It’s a rock-solid airplane,” said Ron, “very strong, over-engineered, rugged, and durable.”

Its airline roots meant it was built with far more safety features and redundancy than tankers from the military. Its by-then total lack of popularity with the airlines made them cheap to acquire, too.

Of course, the transition meant some changes for the plane.

“It was gutted,” said Ron from inside the Spartan cabin. The airplane’s ribs are plainly visible for all to see, while control cables and wiring course across the ceiling.

Notably absent are any creature comforts. “No heating, no air conditioning; that’s all gone. No pressurization,” said Ron. Only a pair of small, metal cage fans in the cockpit remain to keep the crew cool while working long days over summer fires. “It gets pretty hot,” said Ron.

Most of the soundproofing is gone, making it noisy once the engines are running. The lounge in the very back, which once ensconced chatty, cocktail-sipping passengers bathed in cigar smoke, has long disappeared.

“But somebody decided to leave part of the first-class section intact,” Carpinella said, referencing four of the original eight caramel brown seats that remain. The section is a shadow of its former self, yet the luggage rack is still there, full of manuals and other smaller items. The passenger overhead panel is there too. Surprisingly, the reading light dutifully brightens at the flick of a switch.

Behind that, the plane is full of the tools of the tanker trade: ladders, to make repairs and to enter and exit the plane; oil barrels, in case they need their own oil for an emergency; personal effects, since crews don’t necessarily know where they’ll end up for the night; and spare tires.

Other systems specific to aerial firefighting were added, namely the giant 3,000-gallon (27,000 pound) retardant tank. The cockpit looks largely unchanged, filled with dials, gauges, and circuit breakers. Besides the tank-control additions, the only modern pieces are a Garmin GPS system, a new radio, and an iPad flight bag attachment.

“It’s basically a really big crop duster,” said Ron.

Ron and Scot estimate that the airplane has made thousands of drops, in which a mix of red retardant slurry is dropped ahead of and sometimes onto wildfires, in its time. “Nothing like putting a line between a fire and a home and seeing that it saved it,” said Ron.

But a mix of money and politics and the simple evolution of the industry have come to draw the curtain on Tanker 60.

After over 40 years in the air, saving countless lives and homes, the fire service has declined to renew the airplane’s contract into 2021.

Which, as Ron said earlier, makes today’s flight back to its home base in Madras, OR, likely to be its last.

——

A small model of the plane, made by a few former forestry department coworkers, sits just inside the fence at the Medford base. Its orangey-red streamers, mimicking a retardant drop, sway gently in the breeze as a small group gathers around it a few minutes before sending the real airplane off for the last time.

“I want to switch out the streamers to a hot pink, touch up the paint a bit,” one of them remarks before noting the time: 3:45. Tanker 60 has to be out by four; it’s time to go.

The engines puff and chug to life at Ron and Scot’s command, belching out white smoke before settling into a noisy, chattering idle. The ground crew wave it goodbye as Ron releases the brakes and rolls the plane off the tanker ramp.

Taxiing out to the runway, it is apparent that both the plane and the pilots have achieved minor celebrity status. “It’s a kind of icon during the summer,” said Ron.

Commercial flights slow-roll by, their pilots staring out the window as long as they can to gawk at the four-engined vestige of another era. The airport tower, along with other flights in the area, call in to thank the crew for their service over the past season.

“I think to some folks it means a lot to see it there in Medford,” said Ron.

Tanker 60’s last season was a particularly brutal one, especially for its home base of Medford. Two major fires burned in or near the city in September, both easily visible from the tanker base.

“I feel we get a bit more credit than we deserve,” Scot said after the flight. “The real credit goes to those on the ground, who literally fought the fire at arms length.”

The suburban Medford towns of Phoenix and Talent, OR were devastated by the Almeda Fire. “It was one of our last assignments,” he said, before adding that it also happens to be where he and his family live.

“When we did our first drop, I could see my wife and daughter in our yard hosing down the house,” he said in a post-flight talk. “At that point I just assumed the house would be gone.”

Scot’s house ended up surviving, but the fire leveled much of his neighborhood. All told, it killed three people and destroyed over 2,800 homes and businesses according to local officials. “It consumed the bulk of the town,” said Scot.

“To see those efforts and to hear about the challenges the folks on the ground faced while attempting to save the lives and property of strangers; that is what gives me a cherished sense of pride,” he said.

The engines throttle up to a dull roar, tongues of fire spitting out of the exhaust stacks and across the wing as Tanker 60 accelerates down the runway. The smell of oil—normal in such airplanes—is unmistakable, and the cabin shakes with bone-rattling vibrations.

Ron eases the airplane into the sky, tipping the wing toward the tanker base in a nod of thanks to the hard-working crew.

It is a short flight to Madras, only 180 miles as the crow flies, and both plane and pilots settle in. Ron and Scot point out locations of previous fires along the route, recalling drops from days past. The late afternoon sun casts glorious golden light across the forests, fields, and mountains below.

The airplane lumbers low over Crater Lake National Park, the deep blue water sparkling. It isn’t hard to imagine the tourists down below stopping to gawk. “No one ever complains about our noise,” said Ron.

Were it not so beautiful, the flight would otherwise be downright pedestrian for a plane that normally flies over literal fire.

Thirty minutes later, Madras comes into view through the windshield. Ron lines up Tanker 60 with the runway but stays high, executing a maneuver known as an overhead break with a graceful bank over the airport before looping around to land. It is a maneuver common to homecomings, dating back to World War I aviators returning to base from a mission.

Ron and Scot put the plane down gently, rolling to the very end of the runway as if on a leisurely stroll.

There is no water canon salute, and no crowds. Only a few people from Erickson Aero Tanker and an aviation enthusiast that drove up from Bend, OR, are there to greet it as it rolls to a gentle stop in the waning light of the day. The engines shut down, and the cabin noise fades to nothing. Ron stretches out a sore back before unpacking, while Scot finishes the last entry in Tanker 60’s logbook.

For the end of an era, it feels remarkably anticlimactic.

“To lose it is to lose a bit of history,” Scot says on the drive into town, “I feel like I’m watching evolution.”

“I don’t want to get too cosmic,” he said, “ but I feel like I’ve witnessed it take place; watching one thing come to an end.”

Erickson Aero Tanker plans to keep the plane in tip-top shape over the winter, just in case fire officials reverse course. The company estimates they have enough spare parts to keep it going for another five to ten years.

“Regardless of whether it comes back next year, or the year after, its days are numbered,” said Scot. “And I feel privileged to be a part of it.”

Still, barring a small miracle, its contract will end and its flying days are done.

Turns out the fire service is doing the same thing now that the airlines did fifty years ago: moving on to jets.

A version of this story originally ran on BusinessInsider on Oct 28, 2020.

Photos & video by Jeremy Dwyer-Lindgren.

Photo from Almeda Fire provided by Scot Douglas, Erickson Aero Tanker

*January 2021: The airplane has since made a handful of short flights, part of upkeep in case its contract is renewed or a new owner is found.

*June 2021: The airplane’s contract was not renewed. Erickson is seeking new owners.